NEWS & INSIGHTS

Technical Top Tips | Meetings: Chapter 1 - The Chair

The Wexted Technical Top Tip Series

The Wexted Technical Top Tip Series will be examining specific issues related to the management of insolvency and restructuring assignments, and our first mini-series will be on Meetings.

The running of a formal meeting is, of course, a critical element of a successful insolvency or restructuring appointment. In a contested environment such as insolvency and restructuring, it is of course necessary, for public confidence, that decisions are made based on proper principles including:

- A predefined agenda, and a scheduled time and place;

- The acceptance of designated roles (chairperson, secretary, etc.);

- Rules and accepted rules of procedure;

- A process for Minutes record-keeping and public dissemination of that process;

- A clear decision-making authority.

Whilst there are many rules and Procedures relating to Meetings (such as Division 75 of the Insolvency Practice Schedule CORPORATIONS ACT 2001 - SCHEDULE 2 Insolvency Practice Schedule (Corporations) those regulations relate to tangible matters associated with creditors and committee meetings, the giving of notices, the admission of claims to vote, and so on. They do note provide any practical support in relation to the various non-insolvency procedural issues and conventions, nor the more intangible issues that participants should understand and keep in mind, which are becoming more important as restructuring processes evolve.

First, some history!

History of Meetings

Meetings have, of course, been held for thousands of years, as long as the very earliest organised societies and languages emerged.

Ancient and early civilizations, where the very first bureaucracies were created, needed a form of administration to manage temples, grain storage, the application of laws, taxation and trade, and punishment. Written records (such as cuneiform tablets) show signs of early organised decision-making processes.

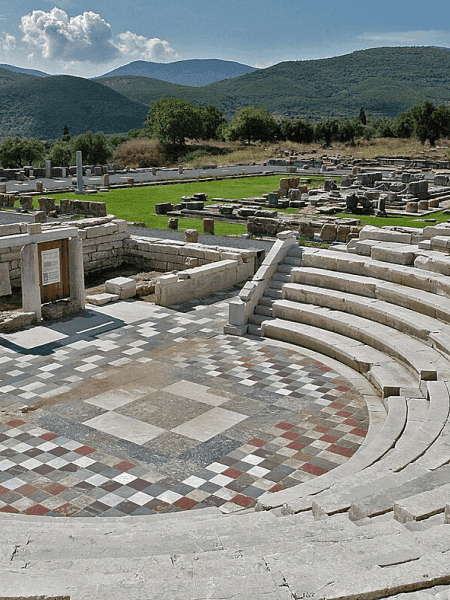

The Athenian democracy (c.500BC) is one of the clearest examples of formalised meetings: citizens held structured assemblies (called Ekklesia) with agendas, debates, and votes. Meetings followed rules of order and often took place in designated locations, such as the Ekklesiasterion in Messene.

In the Mediaeval period, Feudal Courts formalised proceedings and councils for governance actions. The witan (lit. 'wise men') was the King's Council in the Anglo-Saxon government of England until the 11th century. It comprised ealdormen, thegns, and bishops, with meetings called the witenagemot, advising the king on legislation, judicial cases, land transfers, and other matters of national importance.

In the early modern period, England’s Parliament (established in the 13th century) evolved into a highly formalised system with structured meetings. Trade Guilds and Early Companies also held formal meetings with minutes, officers, and rules.

The Industrial Revolution and growth of corporations made formal meetings central to business. Roberts Rules of Order (first published in 1876) standardised parliamentary procedure in English-speaking countries. The purpose of the book (still in publication) was "to enable assemblies of any size, with due regard for every member's opinion, to arrive at the ‘general will’ on the maximum number of questions of varying complexity in a minimum amount of time and under all kinds of internal climate ranging from total harmony to hardened or impassioned division of opinion".

Today, of course formal meetings are embedded in governments, businesses, nonprofits, and all types of community institutions, with well codified practices.

The Chairman

Meetings and assemblies have traditionally had a presiding officer or rotating leadership to control debate, traditionally (of course) this was a king, or bishop in an Ecclesiastical setting. In more modern times, and according to Roberts Rules, the Chairman was established as the neutral presiding officer responsible for:

- Open the session at the appointed time and call the members to order.

- Announce the business to be acted upon in the order in which it is to be considered.

- Recognize members entitled to the floor.

- State and put to vote all questions that are regularly moved or arise in the course of proceedings.

- Protect the assembly from frivolous or dilatory motions by refusing to recognize them.

- Assist in expediting business in a way compatible with the rights of the members.

- Enforce the observance of order and decorum among the members.

- Make decisions on points of order, subject to appeal to the assembly by any two members.

- Inform the assembly on points of order or practice pertinent to pending business.

- Authenticate all acts, orders, and proceedings of the assembly declaring its will.

- Declare the assembly adjourned if necessary, in case of fire, riot, or serious disorder.

The chairman's role is to facilitate the meeting and ensure that it proceeds smoothly, fairly, and effectively in accordance with the Rules of Order.

In case of fire, riot, or very serious disorder, or other great emergency, the chair has the right and the duty to declare the assembly adjourned to some other time (and place if necessary), if it is impracticable to take a vote, or in his opinion, dangerous to delay for a vote.

Roberts Rules, 1876, Paragraph 58

Modern Times

The role of a Chair has, of course evolved. We make some observations below (with the assistance of Joske's Law and Procedure at Meetings) that are generally consistent with the role of a Chair in most corporate scenarios:

Election

- Rules of most bodies provide for election of a Chair. The Chair must ensure they are able to and are seen to take an objective viewpoint on all issues, and do not exercise a vote, unless it is in the Rules.

- For example, a scenario where an expulsion is being considered, and the Chair is the accuser, it is not appropriate to preside. In general terms, the rule is “one may not judge one’s own cause”.

- Subject to the Rules, a person can nominate themselves as Chair but must not merely declare they occupy the Chair.

Duties

- Preside: The authority is not a dictatorial power, but merely the ‘first among equals’.

- Conduct Proceedings regularly: Make sure proper notice is given, a quorum is present throughout, speakers are called by name, debate is conducted impartially, rulings are made on matters of procedure, ensure no discussion without a motion.

- Determine the sense of the Meeting: The ‘sense’ of the meeting should be ascertained in relation to any question, and opposing views must be presented. There is no implied power to adjourn a meeting to avoid a decision. The Chair cannot direct what is to be done, or disregard the opinion of Members.

- Preserve Order: Preserving order is to both prevent, disorder, but maintaining order through protocol, to further the objectives of the Meeting.

- Adjourn if necessary: In the normal course of events the Meeting will determine its adjournment, but the chair is given that power in circumstances (disorder, lack of quorum, etc).

- Control the voting: Ensure all entitled to vote have an opportunity to do so. Understand the poll provisions and be ready to use them. The Chair may have a casting vote on some motions, but there is no casting vote in common law.

- Declare the Meeting closed.

- Sign the Minutes: The Chair vouches for the correctness of the minutes by signing the record.

Interaction between meeting and the Chair

- Point of Order: A point of order takes precedence over a pending question, if it is one that genuinely requires attention. The Chair will normally rule on a point of order without debate.

- Appeal: Rules may give Members rights of appeal from a ruling of the Chair in circumstances.

- Review of Performance: The Meeting may have the power to censure the Chair or request the Chair “surrender the gavel”.

- Removal: Absent an express provision, the presiding officer has no definite term and may be removed at any time, by nominating another person.

Conduct of Debate

- Assignment of the Floor: The Chair should control the assignment of the floor, ensure members are addressing the motion, and be capable of resuming the floor at any time.

- Participation of non-members: The Chair must understand the circumstances in which non members are able to be present at and participate. Motions cannot be moved by persons unqualified to vote.

Practical observations

Some more practical observations:

- Start on time: Get the meeting off to a business-like start, explain roles and clarify the purpose of the meeting;

- Arrive prepared: Know the Agenda and have a running sheet. Understand the rules in relation to the quorum, the making of motions, seconding of motions, discussion and dealing with improper motions. The credibility of the Chair is often tested on these issues.

- Be egalitarian: Make your presence felt but make the meeting ‘member-centred” as much as possible. A dominant Chairman will stifle debate. Resist interrupting, just because you know more about the matter than the members. Resist the desire to be technical, or stricter than is necessary for the good of the meeting.

- Be in charge and be responsible: While in the chair, have close by Constitution, By Laws, and other Rules of Order, and be familiar with them. You cannot tell the moment you may need to call on the Rules. If a member asks a point of order, or a specific motion required to decide a point, that should be known

- Manage difficulty head on: If faced with difficulties or challenges to the Order of the Meeting, display leadership for the good of the meeting. deal with difficult members professionally and crisply in accordance with the Rules. Make sure roles and speakers are clearly defined. Reinforce appropriate behaviour.

Remember the objectives of the Meeting. Use your professional judgment. The key principle is that “parliamentary law was made for deliberative assemblies, and not the assemblies for parliamentary law”. That is to say, the procedure is there to serve the meeting, not the other way around.

“The great purpose of all rules and forms is to subserve the will of the assembly rather than to restrain it; to facilitate, and not to obstruct, the expression of their deliberative sense.”

Luther S. Cushing

| Author of Cushing's Manual, a foundational work on parliamentary procedure in the United States

Published 12th September 2025

By Joseph Hayes

Partner